Until now, Schwaz has mainly been associated with the silver mine, which many people visited when they were at school. The exciting trip into the mine and the minting of a coin remain in their memories. However, an exploratory tour revealed that Schwaz has much more to offer.

The town has a rich history, which is explained on free guided tours every Thursday. Maria Egger, an experienced city guide, not only tells historical facts, but also interesting details off the beaten track.

The area around Schwaz was already settled in the Neolithic and Bronze Age. Schwaz was first mentioned in documents in 930/931. In 1170, the Frundsbergs (also known as Freundsbergs) erected a tower above Schwaz, which was later expanded into a fortification. The town's rise to a mining metropolis began with silver mining in the 15th and 16th centuries. According to legend, a maid - the "Kandlerin" - discovered the silver while herding cattle on the mountain pasture in 1409: a bull is said to have scraped the ground with its horns and the silver ore-bearing stones were revealed. Later, Maria Egger shows me that the stones can still be admired above some of the entrances to houses in Schwaz - a sign that so-called "Gewerken" (miners who, unlike the miners, had mining rights) lived here.

The tour begins at the Stadtgalerien. The modern shopping centre in Schwaz stands on the site where the "k. k. Tabakfabrik zu Schwaz", popularly known as the "Tschiggin", once stood. For 175 years, up to 2.6 billion cigarettes were produced in the factory every year.

In the historic centre of Schwaz, the bronze statue of Jörg Frundsberg, the town's founding father, adorns the town hall. The town hall used to be the trading centre of Schwaz and the most impressive non-ecclesiastical building from the mining era: it was built between 1500 and 1509 by the tradesmen Hans and Jörg Stöckl. After it was sold to the sovereign, the highest mining authority was also established here. Also beautiful: the inner courtyard with three storeys and ivy-covered arcades.

Designer Markus Spatzier has his shop opposite the town hall: the Tyrolean designer creates extravagant clothes that also inspire internationally.

During the walk through Franz-Josef-Straße, the history of Schwaz is explained. For a long time, Schwaz did not have a town charter, as there was no town wall and the town was divided into two parts - on one side lived the citizens and tradesmen, on the other the miners. For this reason, Schwaz did not have its own coinage; this took place in Hall instead.

In front of a wide courtyard entrance, it is noticeable that in the past such entrances had to be large enough to park horse-drawn carriages. A sign with an elephant recalls a curious story from the 16th century:

Emperor Maximilian II was given the elephant Soliman as a gift in 1551. It was then shipped to Italy via Barcelona and taken overland via Trento and the Brenner Pass to Tyrol and on to Vienna. Signs with an elephant can be found at many of the stations that this first elephant travelled through in the country. What happened to him? The elephant lived in Vienna for another year, then it died. It was stuffed, and later its bones were even used to make an armchair.

At the end of Franz-Josef-Straße, the imposing parish church of Schwaz rises into the sky. It is the largest Gothic building in Tyrol and is still largely in its original state from 1502. Miraculously, it was not destroyed in the great fire of 1809 and the church remained largely undamaged during the bombing raids of the Second World War. Inside, the three baroque altars (there used to be as many as 14) and a particularly beautiful baptismal font are particularly worth seeing.

The roof truss, which is only accessible as part of a guided tour, is particularly impressive. This masterpiece was built more than 500 years ago from 770 solid cubic metres of wood and is still in its original condition today. It carries 15,000 copper shingles, which were cast in Schwaz and weigh a total of 58 tonnes. Construction took three years and was carried out with the simplest of means. Carpenter Thomas Schweinebacher created a true marvel of carpentry.

Right next to the church is Palais Enzenberg, which was built in 1515 by Veit Jakob Tänzel. The magnificent palace even has a connecting corridor to the church, as this family were great patrons of the church. Today, Palais Enzenberg houses the contemporary art gallery of the town of Schwaz.

The underground exploration leads to the palace's 500-year-old cellar, one of the few remaining of its kind. In the past, it was used to store food, with ice even being brought in from the glaciers to keep the food cool. Today there are old wine barrels, which are no longer used but have a lot of charm.

After the church, we stop at the two-storey mortuary chapel dating from 1504. In the town park, the former cemetery, stands the bell tower. The bells were too heavy for the church tower, so a separate bell tower was built. Schwaz also has its own weather bell, the Maria Maximiliana, which is rung whenever a storm threatens.

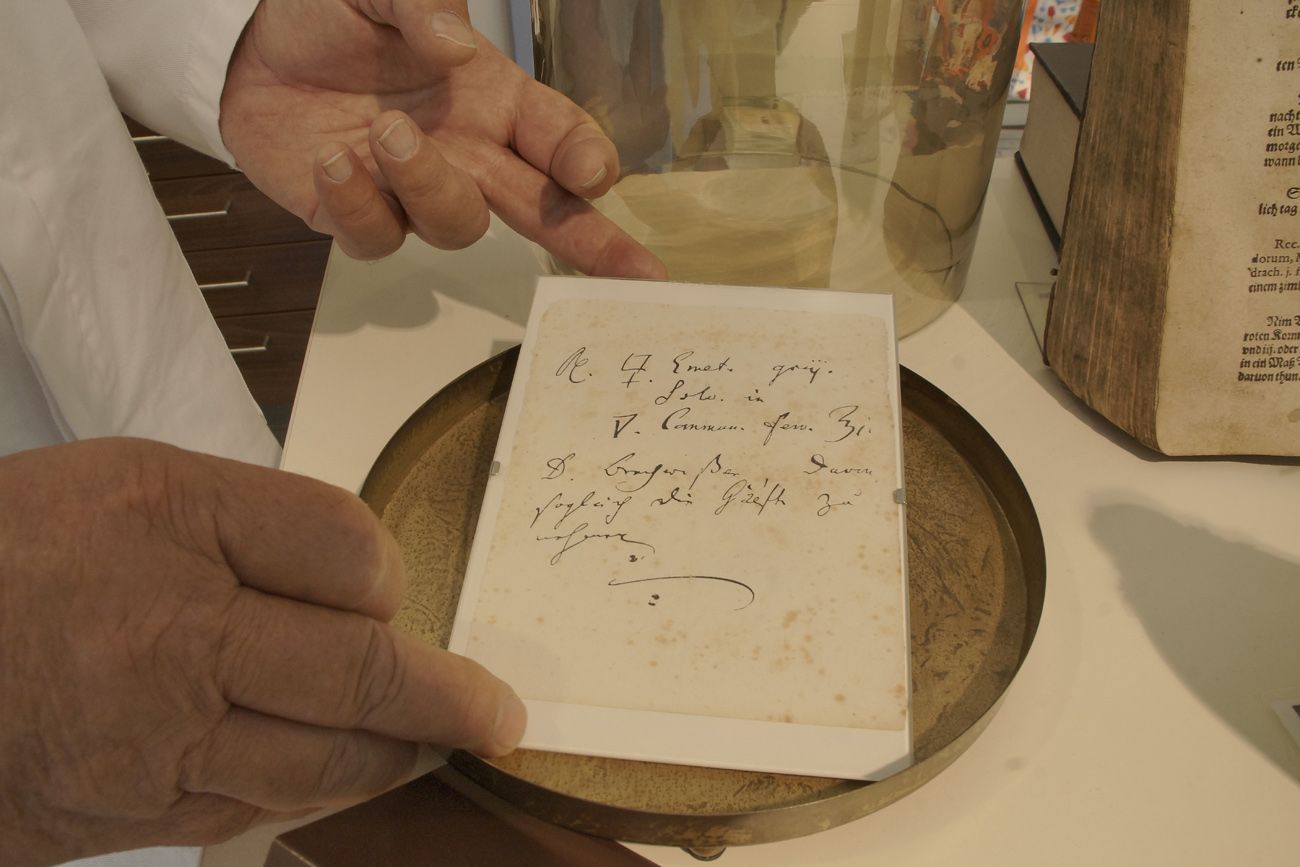

A walk leads across the arcade tombs to the Orglerhaus. This is the only farm that still exists in Schwaz and the famous physician Paracelsus is said to have lived in the house during his stays in Schwaz. The cellar looks exactly as it did in the 16th century, when Paracelsus researched the illnesses of the miners here. Paracelsus was said to have visited Schwaz two or three times. Incidentally, his death is still disputed today. It is unclear whether the powerful Fuggers had anything to do with it - he had fallen out with them through his work.

The Fugger House, with its characteristic moat roof and imposing size, still gives a good impression of the wealth that the inhabitants of the time and the once richest people in Europe possessed. The house itself was built around 1525.

Ulrich Fugger led the family's empire from Schwaz for a time, as it was also the Schwaz silver and copper that made the Fugger family the wealthiest and most powerful family of the late Middle Ages. Today, the house where the richest once lived is now home to the city's poorest: Among other things, the Fuggerhaus houses a tea room for the homeless.

The last stop on the tour leads to the Franciscan monastery, where the cloister stands out in particular. This was skilfully decorated by Father Wilhelm von Schwaben with scenes from the Passion of Christ. The hand drawings were created between 1519 and 1526. Despite restoration, some of them are no longer easily recognisable. Overall, however, they are very accurate graphic depictions from the 16th century. It is also interesting to note that there was a donor for each painting: they are each depicted with a coat of arms - men even with a portrait - in the margin. So you were allowed to choose your "favourite scene" from the Passion, donate a painting and your path to heaven was guaranteed.

Schwaz inspires with its many special features. A stroll through the pedestrian zone always reveals surprises. Finally, we recommend a visit to the silver mine .

The town's former fortifications, Freundsberg Castle, which now houses the town museum and a café/restaurant, towers majestically over the town. The view of the city from the castle is fantastic.

At Gasthaus Himmelhof you can enjoy an excellent meal and enjoy a refreshment break in the shady garden of this cosy inn during a walk through the city.